Monopoly, The Salmon, A Fist Full of Crystals

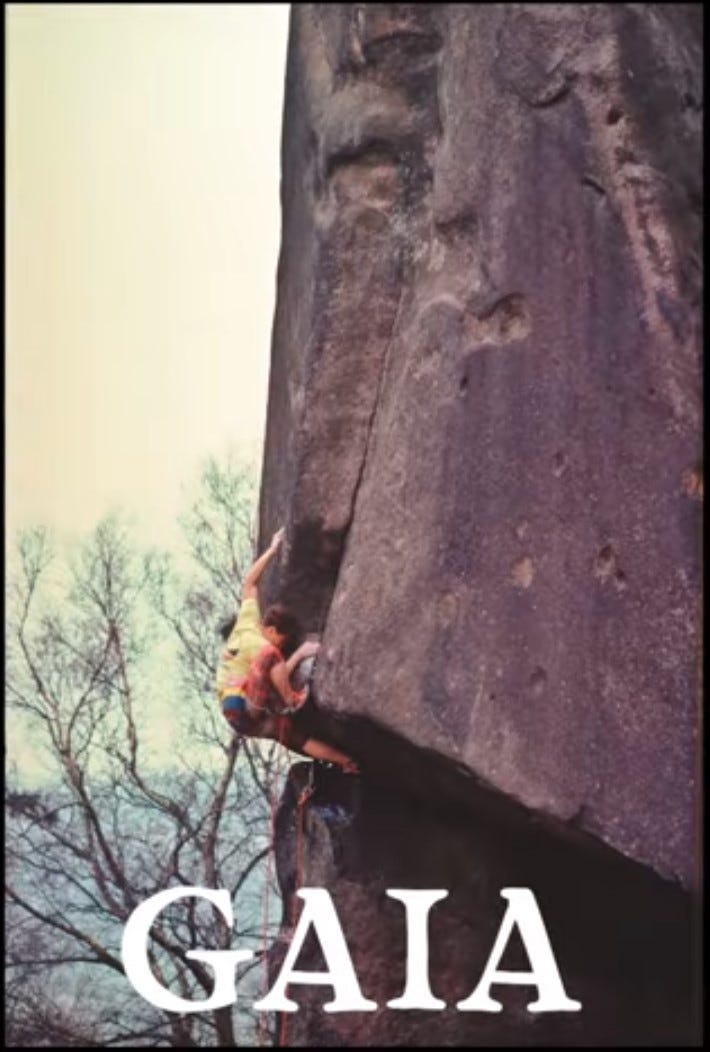

Interviewing the legend of British climbing Johnny Dawes

Not posted in a week or so because was trying to get this profile right. As you will be able to tell I think Johnny Dawes is one of the most interesting people, not just in climbing but in general. Thank you very much to Johnny for his time and wonderful conversation. I don’t use Instagram but I am informed he is good on it, so follow him @johnnydawesofficial.

Sport is fun to follow is because success is so easily understood. When someone gets a Nobel Prize in physics, you don’t think, that’s the best physicist in the world. But when someone gets the Ballon D’Or, you do more or less think, that’s the best football player. It’s the paradox of receiving consistent and regular exposure to that which is out of the ordinary. Sport is thus a kind of managed shock.

When Johnny Dawes climbed The Indian Face in 1986, it was shocking. The route goes up a cliff on the north side of Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon) in North Wales. As the sun sets, the last part of the cliff to be illuminated is a crisp slab that shines back out across the valley. It looks so smooth and unrewarding — ‘a blankness fit for eagles’ —that you can’t help but wonder who you would have to become to make it up there. In the absence of footholds, feet smear against the rock, and hands desperately search for edges to latch onto. The holds you find are as thin as rumours, and for large sections a mistake means death.

It had been tried and flirted with by many of the best climbers around, until Dawes finally put it to bed, giving it the previously unheard-of grade E9. He called it ‘a real trouser-filler’. And this was in a period in which trouser-filling was not uncommon. In the 80s, sport climbing, a safer style where the climber is protected by bolts drilled into the rock, was taking off, and, dialectically, flippantly, punkishly, the trad climbers — who protect themselves only with pieces of metal inserted into cracks — leant into the character of death-baiting lunatics. The trad climbers were not as professionalised and performance conscious as the sport climbers: they were on the dole, sleeping under boulders and raving in barns, shoplifting dinners, climbing with various species of hangover and smashing their ankles. Characteristic of the time was John Redhead, an artist and climber who said gnomic things about the purity of climbing, the call of death, and the evil of bolts – even though he famously drilled a bolt in on The Indian Face. He gave climbs names like Raped by Affection, Tormented Ejaculation, The Burning Sphincter. Somehow, over and above all this tumult, this ambient buzz of shocking behaviour, Dawes managed to shock one time further: The Indian Face, E9.

But none of this is what makes Johnny Dawes interesting. Saying Johnny Dawes climbs dangerous and difficult things is like saying Pavarotti has a loud voice. There’s an art behind the body that you shouldn’t miss. If you edited a video of him climbing, and replaced his limbs with lines and his hands and feet with simple dots, you’d still be able to tell immediately that it was him. In the 80s, people were getting into ‘training’. Sport climbers were growing bigger biceps and stronger fingers. But Dawes didn’t find this particularly interesting, and followed his own path, whose effect you can see in how he treats the rock. He pushes it, tickles it, slaps it, rubs it, kneads it, kisses it on the cheek, punches it, calls it names. Where other climbers go up, Dawes goes across, down, backwards, then appears at the top.

Dawes submits himself to the shapes dictated by the rock. ‘The rock is full of pattern and full of cadence and full of phrasing and a consistent algorithm which expresses itself according to geology’, he explains. The climber is subject to two forces, gravity and friction, which are both independent of the climber and in dialogue with each other. “That dialogue,” he reflects to me, “seems sublimer than either the rock or the person that's involved in it”. Then he takes a second, and grins. “We’ve really gone full wank there.”

It is wank, but that doesn’t mean it’s not articulating something important. When Dawes talks about friction, about submitting his body to friction’s demands, he is reversing the way that agency is usually described in sport. There are some sports people – like Magnus Carlsen, or the greatest competition climber ever, Janja Garnbret – who go in God-mode. When they win it’s because they are imposing their will on a reality which is intransigent and unplastic to the rest of us. But there are also those that Dawes calls ‘olliers’. To do an ollie, you need to time your movements to create fleeting grip on the skateboard which then moves it through space. You work backwards from the desired final motion to the way your body needs to be shaped to manifest it. ‘Olliers’ are people like Dawes, who perform by making their body responsive, conducting force rather than commanding it. I ask him who else is an ollier; he lists Mikhail Tal, Freddie Spencer, Toprak Razgatlıoğlu, Larry Bird, Naoya Inoue, Nick Kyrgios.

As an ollier, Dawes didn’t train in the way that climbers train now. If you climb by surfing the crest of the wave between friction and gravity, getting big strong arms and shoulders is nice but not quite the point. He tried it for a bit: when he was 17, the young Johnny Dawes could do 77 without getting off the bar. But it was not what he wanted. ‘The point was to climb rock by deep invention, experiment and invention,’ he says in his memoir, Full of Myself, ‘not just grunt. To make it come alive.’

He’d found himself at boarding school in Rutland, and it was there that he figured out what he could do for climbing and what climbing could do for him. Born in 1964 to a wealthy Midlands family, he grew up in a 12th-century hall in Worcestershire, whose floors he cycled on and whose walls he bouldered. His schoolmasters introduced him to climbing on actual rock, taking him to the gritstone edges of Derbyshire on weekends. ‘At Froggatt edge,” he remembers, “the blankness generated a strong gravity of its own in me.” Desperate for more, he and some friends would make the forty minute cycle from school to Slawston bridge, often called ‘the only climbing venue in Leicestershire’. Only a connoisseur or gagging school boy could mistake this railway siding for ‘a climbing venue’.

When I talk to Dawes, he is at home in Worcestershire – no longer in the 12th-century hall. On the internet, Dawes is often filmed in tweed with a deerstalker, a shambling yet graceful cartoon, but today he is dressed down. He smiles a lot, very often out of the side of his mouth, smirking either at the genius or stupidity of what he has just said – he’ll never tell you which. He is an interviewer’s dream, dishing up a giga-buffet of ideas, not minding which you linger over. He has no qualms about being combative, controversial, pretentious, or self-mocking. He begins by talking about how well he slept, which isn’t always the case. “Sometimes I wake up at like 3:30 in the morning. I can't get back to sleep. My body's twitching and things. I don't know, it's like old school tension in my body. Really old tension.”

Given Dawes’ biography, it makes sense that he would associate twitching and tension with his own deep history. His childhood was structured by searching for an adequate object for his energy and curiosity, and often being frustrated. At school he was clever but bored by lessons. He was short, not very confident, and his weird manner meant he was ‘ostracized’. But he could climb up drain pipes, out of windows, traverse the micro-edges of the brick walls. Some of this was even difficult. “At school I did one the back of a fives court right up the middle,” he tells me. “Andthat was like, 8a ground-up. 30 foot-fall. Back in 1981. That was the hardest route in the world at the time, I've no doubt.” The cliché would be that climbing was Dawes’ escape, but it’s a funny sort of escape to spend your time feeling up and obsessing over the thing – the school and its buildings – which you want to leave. In truth, you don’t escape something by climbing it, but instead know it more intimately. The wall he was climbing “felt like an undulating porcelain sheet, my body on it a porcelain ball. Separate, inseparable.”

When he left school, working in a factory and then ‘studying’ for a degree in Manchester, he passed days on end at places like Stanage, Curbar, Froggatt, becoming a virtuoso of the climbing on the gritstone edges of the Peak District. It’s hard to explain to non-climbers how a rock type can have such a distinctive identity. It’s like how wines have terroir, the way a landscape’s history creates a background flavour, an subconsciously-grasped character, that throws the foregrounded experience into relief. The terroir of gritstone is jangling nerves, grip-defying rounded holds, endless balancing, legs and elbows shoved into cracks. It is hardmen from Sheffield, disrespect, sandbagging. On a grey day, the rock looks black and surly, but in winter sun, it turns orange as embers.

In climbing, the word for danger is ‘boldness’. The climbing culture in the UK is notoriously ‘bold’, and that is most probably a consequence of the fact that it was - in a way - invented on these tiny gritstone edges. Quite simply, there just isn’t a lot of rock, and so British climbers grew protective of the lingering feeling of wildness and madness that are left on the cliffs. At most gritstone edges, you can hear a nearby road. From some, you can see Sheffield. These are not wild places. Many of them have been quarried. And yet if you were to drill a bolt into a gritstone face, you would have bricks thrown through your window. It would be a denigration of the rock’s majesty. Consequently, at the serious end of the scale, climbers are often dealing with blank slabs of grit, pinching tiny pebbles that stick out from the surface, and face the potential of hitting the ground which is both close enough to be dangerous and far away enough to be dangerous.

Gritstone is the only type of climbing where you can be sitting at the bottom of the crag eating a sandwich, chatting about which route to do next, and someone will point to something out and say ‘I might try that one. At least it’s got a good landing.’ At other times, you don’t choose climbs because you will have only broken your ankles when you fall off.

Being scared on gritstone is just another, perhaps darker, form of submission you make to the rock. Your humanity is softened. Your heart beats louder. You do what is asked of you, and you are also uncontrollable. “Fear,” Dawes writes, “has shown me the animal I was born into”.

Open up a guidebook for any gritstone edge, and you will find Dawes’ routes all over them. Open it up at the crag, look up at the rock, and you’ll get dizzy. It’s usually the blankest, most improbable lines that seem to have his name on them. Perhaps the archetypical Dawes gritstone route is The Angel’s Share at Black Rocks. There is literally nothing to hold onto or stand on. It’s pure grip. There is no point doing it with a rope, because the rope has nothing to attach to. So you simply go up the face of a vanishingly clean boulder, using your momentum to create friction, knowing that if you stop to think you’ll be crunched down at the bottom.

I was recently at Gardom’s Edge in Derbyshire, and looked up at Charlotte Rampling, E6. This is by no means one of Dawes’ classic routes, but it made me sweat looking at it. It can only really be done as a solo, and involves placing all your weight on a diagonal sloping ramp, hence the name. Below are spikes of quarried grit, ready to break your legs if you fall. The names of his routes often capture something about loss, as if life were not that important after all: Angel’s Share, of course, but also The End of the Affair, Sad Amongst Friends.

Because gritstone has been climbed on for so long, and because of the density of routes, the few lines that remain unclimbed become deeply mysterious. One of these is Wizard Ridge, at Curbar, which he has tried off and on for decades. Why has he or no one else ever climbed it? By way of an answer he explains the sequence to me: “Well, you start off in box splits, and then you come across and then you get a splay, two-nail hook, and you sort of dino around that and get an edge and you share”. Sounds hard, I think. But as he continues to explain I realise that, while it is hard, and still technically unclimbed, but there is also a way in which it has been mastered by Dawes, by his language, by the way he talks about it. ‘All the time you're on these terrible two footholds, so any jolt will rip your feet off’ — and here comes the Dawesian moment, the body changing its nature for the rock — ‘and so you've got to be incredibly soft.’ He searches for language that will capture the sequence. “I really like some of the words that point to coalitions in technique,” he explains. “Like fast, or sound.” He mentions other auto-antonyms, such as cleave, moment, cast, set. These words, in that they are meeting points of opposing meanings, are like Dawes’ climbing, which is the meeting point of upwards friction and downwards gravity.

Sure, Johnny Dawes is a sportsman. We can measure what he’s done, manage the shock of it. But there is also all this other stuff. What do we do with all the rock-hugging, the ollying, the wordplay? How does it all fit in? Is it all beside the point to the sheer fact of his climbing?

We can get to an answer if we consider again what is the particular character of climbing. On the one hand, climbing is natural. As Dawes put it to me, ‘people have always wanted to climb. It’s a pre-existent sport. That's what's good about swimming and climbing and fighting.” But the fact that it’s pre-existent doesn’t mean that its structure is simple. With most other sports, you can identify something which is the ‘aim’. In running, it is to go fast. In weightlifting, it is to lift heavy things. In football, it is to score goals. But what is the aim of climbing? No doubt you’re thinking it’s to climb up a rock. But it’s not: there are many ways up a rock, and climbers rarely take the most sensible one. If the aim was to get to the top a ladder would suffice. Then maybe it’s about doing the most difficult moves? Well, not really either. The hardest climb on a particular piece of rock will usually be something silly, like going upside-down, feet-first, zigzagging.

The question about the purpose of climbing gets harder when you get to the specific subculture of trad climbing. Traditional climbing is about two ideas in theory: that no one has to have been up before you, and that you leave no trace after you climb. This is an ideology of self-sufficiency, of questing into the unknown with no external aid. But in practice, this is never the case. Most climbers go up routes someone has already done, consulting guidebooks to know where to go. Leaving no trace is similarly false, because there is always some marker of your presence: it could be metal rings used for abseiling, it could be the dirt you clean off the holds as you climb, or the chalk you leave as residue.

In climbing, what fills this vacuum of defined rules and absolute arbitration is style. If you don’t know what you are aiming for, make the manner of your aiming independently worthwhile. Instead of do or don’t do, in trad you can select which of the rules matters most to you and use them to show your personality. When someone says they’ve done a hard trad climb, we don’t just ask them whether they got to the top while placing all their own gear. We also ask: how many times did you practice it? Where did you place the gear? Were you wearing nice trousers? The style of your ascent is determined by the specific family of questions to which you answer yes. Your style is simultaneously a product of anarchic self-expression – how did you choose to do it? — and total conformity to law – did you stick to the rules you chose? ‘We freely interchange the idioms of will and determinism from moment to moment of an ordinary day’, writes Jeff Dolven in his book about style. Style is thus law and freedom in superposition; it is auto-antonymic.

Dawes takes this concept of style to the limit, imposing onto himself the most whimsical and arbitrary rules he can think of. In recent years, he has become particularly famous for his ‘walks’, or in other words, his climbing without hands. What this involves is showing up to a cliff, and – presumably to the bemusement and humiliation of other climbers – going up a bunch of routes without touching the rock with anything other than his legs. In the UK alone he has done more than 1600 walks, essentially pioneering it as a national discipline, albeit a niche one. Given my level of climbing, I can barely imagine what it would be like to do an E8. Dawes has walked up one: Obsession Fatale E8 at the Roaches in Staffordshire. He has also done one hand, one leg, no feet. I ask if he has done no eyes. “Yeah, quite a lot,” he says. Climbing under these restrictions is style taken to its extreme. I don’t see all this no-hands and no-eyes stuff as a satire on the arbitrariness of the rules of trad climbing. I see it as an affirmation of trad climbing’s love of style, of its elevation of how over what.

When Dawes talks about other climbers and their climbs he never says they are ‘hard’ or ‘dangerous’, saying instead that they’re ‘interesting’. Charles Albert climbing without shoes is ‘interesting’. Alex Honnold soloing El Capitan is ‘interesting’. Saying this seems to be his subjective approval of the style of what they’re doing. In other sports, the interestingness of the method used to achieve something is an asterisk to the main point. The fact that France bored the world to death to win the 2018 world cup is a secondary comment after noting that they won it. But trad climbing is particular because style is more or less, once you know enough about it, the only method of appraisal. I think Dawes was the first person to really understand and articulate this.

Dawes still climbs. He still thinks about climbing, and writes about it. He is still thinking about what the next milestone of style might be. “The sort of stuff that I dream about is climbing on really, really loose, rotten buildings,” he says. “I haven't done that for a long, long time. But I used to imagine it where everything was breaking just as you grabbed hold of it.” When he first said this to me, I thought it was an amazing stylistic ideal: the climb only exists for the moment of climbing, and then it crumbles and breaks down. Now when I read it back, I also hear something elegiac. Dawes is 60, doing more reflecting than climbing these days. It is hard not to read the wall falling away from his hands and feet as life itself going by.

But Dawes, despite these dreams, can be content that he had his own triumph over time. There are hundreds of beautiful and forbidding sections of rock in the United Kingdom that carry his names: his routes, his monuments in geological time. He pushed the boundaries of a terrifying and challenging discipline. But most importantly, he saw a sport and he left an art. At a time when climbing was becoming about muscle, shoes, and numbers, he showed it could be thoughtful and sublime and terrifying. A sport for homo sapiens. A negotiation with the universe. There is no Ballon D’Or for doing that. But even so, we still know that Dawes shone brightly. “Everybody else seems to think being mediocre is fucking great,” he harrumphs. “I don't.”

This was such a joyful read and made me really excited about climbing! I'm ashamed to admit that I've historically thought about climbing as a 'sport' and climbers as 'sportpeople', but I loved your distinction between climbing and other sports because of the 'aimlessness' or climbing (or put another way, the multifaceted and self-defined aims of climbing).

I found this really cool because it reminded me of a book I loved (which I can lend, if it's interesting to you) called 'The Grasshopper', written by a Canadian philosopher called Bernard Suits. It defines games as a 'voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles according to rules', and Suits goes on to suggests that in an ideal world, humans would engage in games as the highest form of life because games provide challenges and meaning without the pressure of necessity.

It feels like climbing, at least in the way understood by Dawes and you (and now me), is a pretty Utopian pursuit!

Full wank will !

Really enjoyed this.