Drinking 700 cans of Guinness on the world's best mountain

Don Whillans' raid on Patagonia and the purpose of luxury

There is a microtradition of British innovation in the important field of expedition supplies. It can be traced back to 1754, when James Lind tampered with the meals of some sailors on the HMS Salisbury and showed that those who had lime and lemon juice didn’t get scurvy. The Royal Navy took note, and assembled complicated supply chains to get vast amounts of citrus on their ships at all times, as well as fruit, vegetables and live cattle. From then on, the diets of servicemen and explorers trended towards greater variety and luxury. On his ship to Antarctica in 1901, polar explorer Robert F. Scott carried 27 gallons of whiskey, 60 cases of port, 36 cases of sherry and 28 cases of champagne. He didn’t take so much alcohol on his next trip to Antarctica, and that time froze to death. Mallory and Irvine took 60 tins of Fortnum and Mason Foie Gras to Everest in 1924; whether that helped them reach the summit or not remains a mystery.

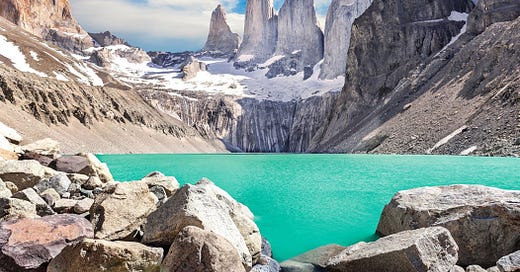

If they were to stand any chance of success, the men on the 1963 British expedition to Chilean Patagonia would need to observe this tradition. Their destination was the Torres del Paine, a triptych of granite towers whose biggest walls drop plumb vertical for 4000ft. They sit in a landscape of fjords that finger in from the Pacific, shattered creaking glaciers and dense conifers blobs that darken the brilliance. By 1963, the South and North tower had been climbed by European teams, but the Central, taller and steeper than the others, was still totally unclimbed. This was the goal. A mountaineer’s eye is drawn inevitably to brutal verticality, to lines that launch up and away in mockery of the body. There are no lines in the world more brutal and more vertical than that of the Central Tower of Paine.

After a week at sea, the team harboured at Punta Arenas, a small city in the Straits of Magellan. They strolled around, made plans, and drank the local beer. Via some cunning persuasion, they had managed to commission the Chilean army — then luckily not engaged any coups or insurrections — to ferry tonnes of food and equipment across the pampas to the mountains. On the back of Chilean trucks they travelled out of the city and arrived in the lower valleys of the cordillera, with deep ravines cutting through knotted gnarled woodlands. They unpacked their tents, maps, and climbing gear. And they got to unpacking their supplies, which did indeed emulate the venerable British tradition of supply: a gilding of luxury on expected hardship. They had whiskey, cakes, chocolate. In addition, as the short film about the trip declares, ‘this modern, lightweight expedition took with it 700 cans of Guinness’. Be advised that there were only 6 men in the team.

They were the inheritors not just of a British tradition of expedition logistics, but also of a British relationship with Patagonia that had existed for years. The Welsh settlers of Patagonia are, of course, well known, but the English too have been messing around in the region since the sixteenth century. In 1586 privateer Thomas Cavendish set off from Portsmouth with the goal of being the first to circumnavigate the globe intentionally — unlike Francis Drake, who had done it by mistake. He reached Patagonia and, after raiding a number of unfortunate settlements by the coast, founded Port Desire, now Puerto Deseado. He then made his way down to and through the Straits of Magellan, shooting hundreds of penguins for food, before continuing up North America. He enjoyed his sojourn in Patagonia so much that he set off for a second raid in 1591, yet on this occasion when they got to the Straits of Magellan Cavendish ate some mouldy rye bread which gave him ergotism, making him wail and hallucinate and generally be a nuisance. Storms hit, supplies ran out, and the fleet became mutinous. Cavendish’s ship separated from the others. Briefly they landed at a small settlement in the Straits but found only six starving inhabitants and little else. Later, this settlement would revive itself, expand, and come to be known as Punta Arenas, the same city at which the British raiders of 1963 would land on their great journey.

Post-Cavendish, British interaction with Patagonia was fairly quiet until the 19th century. After Napoleon booted out Spanish emperor Ferdinand VII in 1808, the colony of Chile achieved a kind of pseudo-independence. A junta took control in 1810 and declared that a number of their ports were to be open ‘to free trade with foreign powers, friends and allies of Spain’. Flooding in came foreign merchants and officers from all over Europe, but particularly from Britain with its seafaring history and colonial infrastructure.

Throughout the 19th century, the Chilean markets for wool, meat and silver were managed largely by British merchants who bought large estancia to raise cattle, and employed the local gauchos to run the herds. Many such families further profited from the Tierra Del Fuego gold rush in the 1890s when land values exploded. It was this lineage of landowners, who traced their origins back two centuries, that supplied the British team with meat and vegetables when they had reached the foothills of the cordillera. As a patriotic gesture, it all came gratis. The men cooked lamb on spits and fried beef flanks. The efforts of these loyal ancestral Britons meant that ‘it was the best supplied trip I had ever been on,’ according to one man in the team.

That man was Don Whillans, a former plumber from Salford, who by the 60s had a reputation as perhaps the most naturally-gifted climber of his generation. He had cut his teeth on the gritstone edges of the North West of England, putting up routes that were flaky, fissile, intimidating — a portrait of the man himself. However, he wasn’t quite regarded as great mountaineer. In the Alps, and on big mountains generally, he had a number of high-profile misses, being often eclipsed by more glamorous contemporaries. He had failed repeatedly, for instance, to get the first British ascent of the Eiger Nordwand, Europe’s best known vertical graveyard. The younger, longer-limbed, Sandhurst-trained Chris Bonington beat him to it. Bonington, as it happened, was also a member of this 1963 expedition to Patagonia.

The above is a photograph of Whillans and Bonington taken at some point in the late 50s. Bonington is the passenger, Whillans is driving. While only a year older than his companion, the difference looks larger, as Whillans is sunken, with lines beginning to form on his face, while Bonington is smoother, a smile shadowing his lip, somehow with a straight back and shoulders despite the cartoonish size of his rucksack. As the caption tells us, the pair were setting off for the Alps. The mind boggles at how Bonington could carry all the equipment needed for a serious expedition in a single rucksack as a motorbike passenger, but it does show that, on this occasion at least, the team might not have had the same expedition luxury as British tradition might require. I have no information about where the pair got their food supplies for this Alpine trip, but it shall suffice to quote Jim Perrin, Whillans’ biographer, explaining how one of Don’s expeditions to Alaska in the 70s was arranged: ‘the provisioning involved a van, a supermarket, and no exchange of cash’. Such behaviour was de rigueur in British mountaineering at the time.

Sitting together on the bike for all those hours and days, winding up hairpin bends, the pair would have had to get on. They had first met in the Alps attempting climbs like the Walker Spur and the Aiguille du Dru, and trips like this initially augured well for their relationship. Yet Bonington’s success, and the speed at which he had achieved it, rankled with Don. In that photograph above, the more talented climber is driving, and yet it will be the passenger who ultimately arrives. By 1963, Whillans was working in an outdoor shop in Yorkshire while Bonington was making a living writing books and for the Daily Express. As far as Whillans was concerned, they were not on speaking terms.

Yet they would have to get along. The Patagonia expedition was scheduled for multiple months, with much of this time consisting of one belaying the other up progressively more dangerous walls. When you’re in the wild, there are only the people around you. Each other person in a team of six becomes Olympian, filling up the sky like the mountains themselves. You feel the twitches of the muscles in your partner’s face as much as rough granite on your palms or dry wind in your eyes. These days, it takes only a few hours to get from Punta Arenas to the mountains on roads built in the 80s, but in the 60s it was true wilderness. For many years, the Torres del Paine were not called this, but instead simply were referred to as Cerro Inominatus — ‘the unnamed towers’. They were so remote and forbidding that it seemed silly even to give them a specific title, as if they would always remain, in some fundamental sense, unknown. And in a place like Patagonia — where the Roaring Forties take run-ups before fly-kicking the cliffs — if a place seems unknown, it usually is, and for very good reason.

This is what Whillans, Bonington, and the four others on the expedition faced. This is what 700 cans of Guinness would have to help them with: the wind, the rock, and the warfare between souls.

Despite all this, the climbing of the Central Tower began fairly auspiciously. It was December, and it looked like there was to be a window of some days in which there was only 10% chance of a lethal storm — otherwise known as ‘summer’ in Patagonia. The team tackled a few lower-lying pitches and fixed ropes to allow them to regain their high point. This is can be called ‘classic’ style: the mountain is not done in a single push from bottom to top, and is not climbed ‘free’, but is attacked in multiple stages with sophisticated tooling. Whillans was climbing well, Bonington being affable as usual, accommodating of his partner’s complex moods.

It took about a week, but they reached ‘the Notch’, which is where the connecting tissue of rock between the North and Central Towers ends, and the Central Tower must be attacked directly. This was the start of the difficult climbing. The team rested, scanning the rock with their binoculars. Soon, they were ready to continue. But Patagonia had different ideas.

‘The weather broke’, as Bonington remembers, ‘and for five and a half weeks we were submitted to what must be some of the worst weather in the world.’ Life became merely a question of survival. They were camping just below the Notch, hearing wind against their tents as solid as fists, expecting at any moment a gust would rip the fabric apart and take them down the slopes with it. They survived one night, then fled back to their lower camp on the glacier. All six climbers crowded in one tent for warmth, eating and smoking and discussing what to do next. For a few days they tried to wait it out, but the tents, even lower down here, were being torn to shreds by the wind. Eventually, they bailed and returned to Base Camp.

Fortuitously, they had returned in time for Christmas. They roasted and ate whole sheep and drank gallons of Chilean wine. For a moment, indulgence meant that they could forget the question of mere survival made real by the storm.

After some days, with the weather still battering the towers, they heard voices coming up from the valley below them. The voices, they soon realised, were speaking Italian. The British invited the newcomers over for a meal. Unfortunately, none of the British spoke Italian nor the Italians English, so conversation was carried out in low-powered French. It was eventually communicated that the Italians had come to do the Central Tower as well, and there proceeded to be some arguing about who had priority on the route. The Italians claimed they had permission from the Chilean government to climb the Tower, and had even promised the Pope that they would get to the top. Whillans insisted that that the British team had already been up most of the way, and if the Italians were going to climb their route they would need to force them off.

Whillans was a difficult person to disagree with. He was 5’3”, but it was clear that he would use physical force, and use it well. Fighting was one of the things Whillans did, and not only with other climbers. In 1975 he was arrested for assaulting three policemen. And it wasn’t just people. Climbing on Creag a' Bhancair in Glencoe in 1960, his progress was halted by an angry nesting eagle. The next day, he returned with a catapult.

Eventually a compromise with the Italians was reached: they would climb the Central tower, but would avoid the route that the British had already established. The weather straightened out, and Whillans and Bonington had another go at increasing their high point. They moved fast in perfect weather, going past the Italian tent from which no sign of life was visible. A rope nearly snapped on Don when he was 50 feet above a slab, probably thanks to weeks of scraping on sharp rock in the storms. Jolted down, it looked like he was going to end up at the base of the cliff, but he spread himself on the wall, and managed to reinforce the frayed and threadbare rope with one hand before climbing on.

On January 15th, everything, including the weather, was ready for a summit attempt to be made. The alarm went off at 0400. Whillans and Bonington drank some coffee and started climbing. They reached the summit of the Central Tower of Paine at 1900. They took summit photographs. The view gives out on the West to the Paine Chico, an indeterminate lump of ice and granite, and beyond it, to strands of the sea encroaching on the land. To the East are the flat plains of Argentina, cow country, miles and miles of scrub cut by North-South highways. It looked warm down there.

After this day, Whillans and Bonington would not summit any great peaks together. Whillans did ascend Annapurna in 1971, but Bonington, while the leader of that expedition, did not summit. Their careers were on different trajectories. While for Bonington the trip to the Patagonia was little more than a warm-up, for Whillans it was already the semi-finals.

So why did he not go on from this? Why did this gifted man not do more with those gifts? Let’s go back to the pair on the final push of the Central Tower. Bonington is holding the ropes, Whillans is climbing. Here is how Bonington describes it:

A cigarette jutting aggressively from Don’s mouth, he balanced up the slab. There were only tiny rugosities, no positive holds, but slowly, confidently, he worked his way up the rock, trending to right or left, seeking out the only possible line. There were no cracks for pitons and retreat would have been impossible. It was now getting late, and an ominous mass of cloud was piling up on the Patagonian ice-cap to the west, a sure sign that the weather was breaking up.

Bonington’s vignette paints his partner as being in a many-splendoured danger. The rock exposes him to the air and then, after the air, the ground. Granite, because it is hard, can have long sections where the surface of the rock has not broken up, meaning that there are no holds or anything to stand on. Ominous clouds signal more of the murderous wind that they have just about managed to survive thus far. And yet Don makes progress, inch by inch, smoking his cigarette.

In the 60s, a climber smoking was far from unusual. But for Don Whillans, the cigarette in mouth as he faces multiple compounding perils looks like more than a mere physical habit. It symbolises something about life, and about death. It was also not unusual for teams to take so much booze with them on trips like this. Yet again, for Whillans, it seems to say something: this life is going to kill me no matter what I do.

The years after Annapurna in 1970 were years of decline. Whillans put on weight and did little significant mountaineering. He became bitter, drinking alone in hotel bars, while Bonington was doing things like summiting Everest and soloing Antarctica’s highest peak. Eventually Whillans died in 1985 at the age of 52 of a heart attack. For a man like him, who spent so much time in the Himalayas and dangling on hemp ropes in the world’s deadliest places, who had so many friends die in avalanches or mangled at the bottom of Alpine faces, there is something impressive about dying in your sleep at home in Cumbria, drunk and obese.

For some people, climbing allows them to get the most from life. Bonington’s 70 year career is no better example of this: on his 80th birthday he climbed the Old Man of Hoy. Yet for others, climbing lets them speed towards death. As a child, Don Whillans’ favourite place to play was the River Irwell that flows through Salford. ‘It was a place that frightened the hell out of me’, he wrote. ‘The water was churned up white and the kids said there were knives under it.’ Some teenagers from the neighbourhood drowned there. And yet he returned day after day as a boy, swimming and jumping from the stout bluffs.

When there are 700 cans of Guinness on an expedition, you can view it one of two ways. You could see it like Bonington did, as an ornament of indulgence and civilisation that make it easier to endure the suffering you know is coming. In this, one can see shades of a stiff-upper lip British tradition, a certain class and ethnic mythos. It is made of the same stuff as Nelson serving claret to his men before the Battle of Trafalgar. It is fine bone china taken to the malarial Raj. You drink your Guinness, you savour it, and you face suffering. On this view, there is a dialectic between indulgence and deprivation. This, I think, was the intention of the British tradition of luxury supply, and the attitude of most of the men in Patagonia in 1963.

If that is the tradition, then there is a counter-tradition. You could view climbing instead not as deprivation relieved by indulgence, but as indulgence by means of deprivation. And there is no dialectic here, for fear and suffering are itself the indulgence. Since climbing is the pursuit of silly, decadent, unnecessary things by definition, you may as well do other silly and unnecessary things while you’re at it. Whillans drinking his Guinness and smoking his cigarette on the cliff, is, for him, a type of indulgence which is of the exact same character as the mountaineering itself. The body goes to its limits and approaches death whose sweet smell hits your nostrils.

Whillans was once asked why he drank so much, to which he replied ‘because I have a morbid fear of dehydration’. A joke, granted, but one that plays with exactly the same idea. Drinking is not an indulgence in tension with climbing or whatever other things you’re doing, but rather, because drinking is ‘hydration’, it is — on this burlesque of logic — the very means by which you will accomplish anything. The indulgence in alcohol and and the indulgence in climbing are essentially commensurate. In the end, only one thing can kill you. Smoking, drinking, climbing, fighting, motorbiking: only one can kill you.

In 1966, some years after the trip to Patagonia, Whillans headed to Yosemite where he met some of the stone monkey dudes putting up lines on El Capitan. One day, he was out with Chuck Pratt. They downed a few six packs, snoozed in the sun, then roused themselves for a route called ‘Pharaoh’s Beard.’ Large parts of the climb were scary, requiring tough moves without protection. The next day Don was ruminating on his partner’s bravery, so went to chat with Chuck about it. After a few comments, Chuck frowned back at Don, puzzled. “Did we do a climb yesterday?’ he asked earnestly.

Let us say simply the following about this story, with a black and teasing irony we may summon from the ghost of Don Whillans himself: drinking and climbing are the same thing, and if you don’t remember the climbing because you’ve been drinking, that just means you’ve done all the more climbing.

Thank you for reading. Please subscribe and like the post, it helps a lot. I have many other posts such as one here about the greatest mystery in the Himalayas, an interview with a rock climber who doesn’t use his hands.

new heights of brilliance! among the many things it’s left me thinking about are the exotic combinations of ‘Smoking, drinking, climbing, fighting, motorbiking’ which actually could kill you at once: motorbiking blind drunk, fighting on a mountain, etc. etc…

Excellent essay. I’m a blue-collar former mountaineer, so Don Whillans was a sort of hero of mine. I’d say Don viewed his climbing trips as holidays. The trades in the UK in the 50s and 60s were grueling.

Any chance to get out of dreary Britain and to sunny France or Switzerland or even farther afield, Patagonia, was a chance to glimpse another world. There weren’t many plumbers in those days on familiar terms with products of the public schools. There’s a famous anecdote of a BOAC captain in the 60s who, upon being greeted by a mechanic, responded with “People like you don’t speak to people like me.”

Whillans would have scraped for his pints, so to have lakes of stout and forests of cigarettes on an expedition would have been very like heaven to him.

My climbing partner in the 80s and 90s was a teacher of physics. At the time, carb-loading was the accepted way to prepare for activities requiring high endurance. He’d shake his head at me for grilling a big old steak over a campfire and having a few beers before we headed up a trail, but I wasn’t going to spend my precious vacation eating spaghetti and drinking Gatorade. Thankfully, I never got into smoking cigarettes.

Climbing to me was about enjoying life in a heightened way and the rest went with it. Now, we have a sudden warm spell here, so I’m off to get a few miles on my motorcycle.

Thanks for a really thoughtful essay, and Happy New Year to you!