I had to do this in multiple parts because it needs lots screenshots, and Substack runs out of space pretty quickly if you do too many images. Sorry!

Also, please like and share the post if you enjoyed it, it is always very much appreciated.

I flew over Greenland on the plane to San Francisco last week, which was the first time I had gone bird-mode in full visibility over one of my go-to gmaps zooms. It was a bit embarrassing, like someone had made too much of an effort on my birthday, baking me a cake and giving me a present. The pilots must have known that I was daily zoomer-inner to the fringes of the Greenland ice sheet, to the big fingers of granite coming out of the firn. With other glaciers, the mountains wear the ice, but here the ice swallows up the mountains.

Of course, while I was on the plane I had Nansen on the mind. These days we know him as the lumbering hero making a near-suicidal dash for the North Pole in the 1890s, but looking down at Greenland, it was hard not to view his successful ski traverse of the whole island, the first ever, as more impressive. Sliding across the ice sheet, he felt flat against it, tiny and oppressed. He never got to see Greenland from the air, never got to get up high and stare horizontally at what he had achieved.

This history is one reason why Greenland is one of the best gmaps places, but it also ticks purely topographical boxes. There isn’t really anywhere in the world with the same character: coastal mountains, ice, some vegetation, human habitation. It is vast, which means there is still the lingering promise of discovery, the idea that you might discover something new from your desk.

Loading up gmaps and flicking around places like Greenland has long been my default mindless habit. I do it instead of scrolling, which maybe sounds like boasting, but it’s not really boasting given that I know it is a fairly common thing. It definitely doesn’t indicate some special virtue of curiosity on my part. Mostly it is nothing to do with curiosity.

While something is loading, or while someone boring is talking, I will load up the maps, and pan and zoom around, simply because that’s what my fingers want to do, just like scrolling is for some people. Panning and zooming is scrolling the earth. On a laptop, it’s a two-finger drag to zoom, which is a gesture I have always liked because it rhymes with beckoning, like you’re bringing the world to you, setting it down in front of you.

One of the most reliable routes to hating yourself is to ask what you have gained from the things you do mindlessly. Were I a TikTok viewer, I’d like to think I’d have the courage to write this post but for TikTok. Who knows. In any case, I thought I would do the exercise for Google Maps, and justify myself to myself.

I realised very quickly after beginning that I did not feel like I knew much more about the world than the counterfactual situation in which I had never looked at gmaps at all. I accept this may sound absurd. But what you must remember is that when I’m scrolling earth, I’m rarely observing features which become knowledge, which become concepts that I can use in negotiating reality ‘out there’. On the contrary, when I linger somewhere on gmaps, it’s often because my expectations which I bring from other types of non-gmaps learning have been violated in some manner, and I’m attending to the feeling of my understanding being changed. Like for example if I find a city looks much bigger than I had supposed, or some mountains in the southern Rockies have no snow, I will be surprised. The surprise is what grabs me, the sense of rupture. I don’t think gmaps has taught me about world, but it has taught me about how I have represented the world badly.

“Philosophy is essentially world-wisdom; it’s problem is the world”, says Schopenhauer, who was, of course, a gmaps superuser.

1. All mountain ranges look smaller than you think they should

When you’re on the Mont Blanc massif, for example, you can look 360 degrees around you and just see more and more Alps.

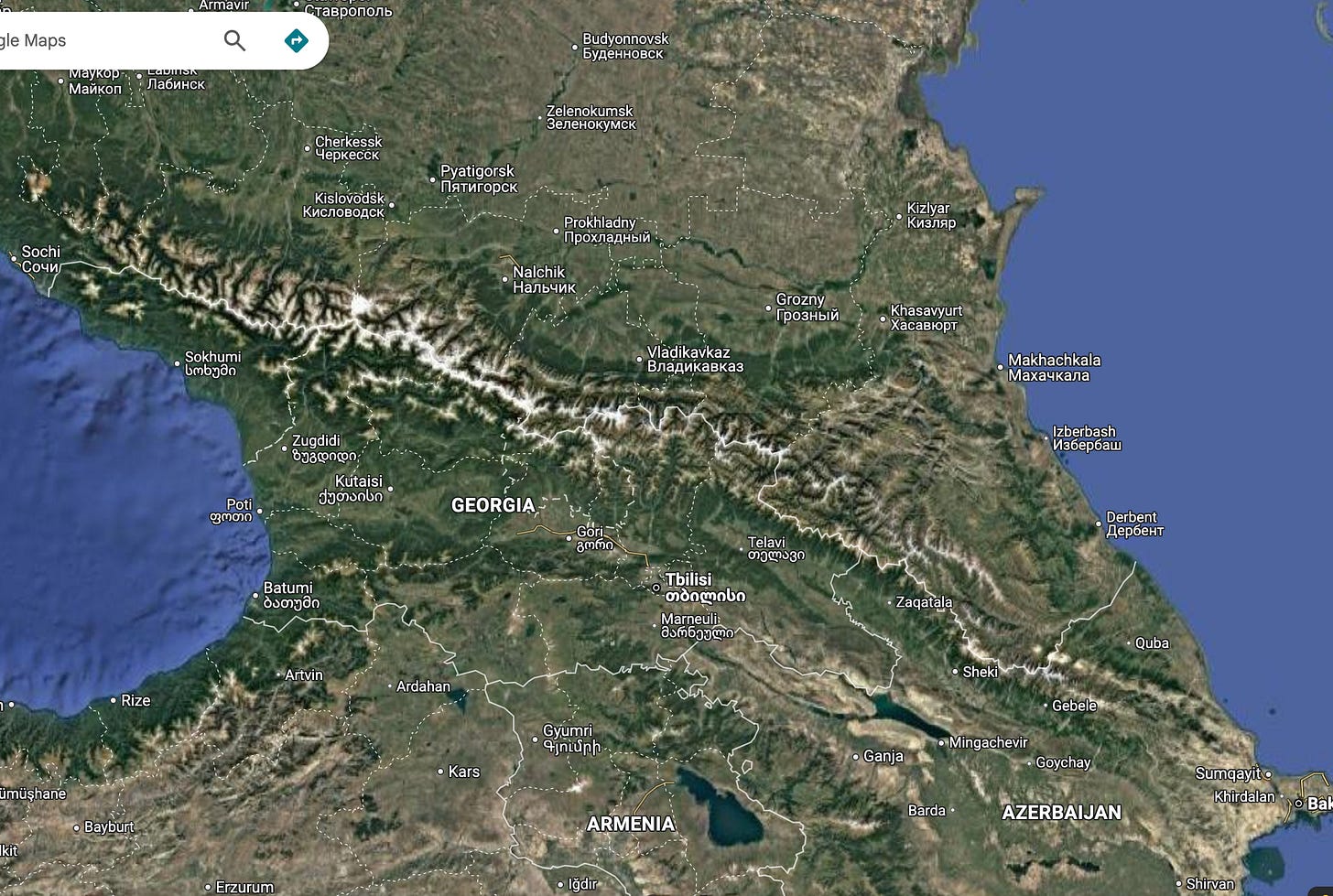

The Caucasus, a noble range, looms large above the Black Sea and Pontic-Caspian Steppe. It also looms large in Russian and Soviet history. And yet on the map, it is basically one single line, one wrinkle. It is one lump to surmount, and once surmounted it looks like you can just cruise all the way to Tbilisi and do what you like there — a historical notion which has been infamously and disastrously entertained.

Mountains in satellite imagery lure the eye to the highest points, those with snow-white highlights, and because the surrounding landscape is greeny-brown the mountain range is rendered in silhouette. Only the extreme points are seen. Any mystery in twisting paths, wilderness, hidden valleys, dark forests, is lost.

If this is true about the Caucasus, it is ten times more true about my favourite mountains, the Scottish highlands, which look like little more than a tabletop smear of grease from this angle.

Yet this phenomenon is not all bad. Minimising mountain ranges on maps is an effective way to dodge the world-scale FOMO which always comes about when I remember that there are approximately infinity mountains out there which I will never visit. It’s bad enough knowing that the Drygalski range of Antarctica exists. No more of this please!

2. Mountain ranges with no StreetView/Sphere coverage are tantalising

The converse of the above is that when you get a large, snowy mountain range, which even the gmaps view cannot minimise, and that range has no PhotoSphere (the panoramas not on the roads) or StreetView coverage, the FOMO is multiplied times a million.

When you’re browsing gmaps on a dreary day, trying to ignore whatever annoying issue you shouldn’t be ignoring, it is hard for the pastime not to become wishful. Sometimes, you find yourself living dangerously, and not only yearning for the places where you zoom, but zooming into places that you know you will never be able to visit, and yearning for them, which raises the power of yearning factor. It’s one thing thinking about heading off to Wales while you’re bored in London, but it’s another to be checking out landing strips on Baffin Island. Places with no on-the-ground imagery, but which look huge and impressive, tempt you with the idea that maybe you could be the one to make it there.

The best way to deal with this is not to ignore it, but to do a bit of exposure therapy. There are places which can blast you with mystery and uttainability, the best of which is Tian Shan. This is one of those places that falls into category of plausibly-could-go-realistically-will-never-go. There is no StreetView coverage, and barely any PhotoSpheres, so instead I have to look at the satellite, at the range’s shape, the way seems to incubate every type of biome in its weird sprawl. That’s a lot of things never to see.

3. The satellite coverage can be good in surprising places

The Tian Shan satellite imagery is passable, but it’s not good enough to plot a land invasion of China — which is no coincidence. If that is something you’re interested in, the best resolution imagery tends to be in places which produce a lot of Google’s revenue: in other words, wealthy urban areas. In Manhattan you can see people’s hands and shoes.

There are some exceptions to this, which means you should always be prepared to be surprised by pockets of very high-resolution coverage. For example, in Rural tibet you can see individual telegraph poles in the desert.

These poles are taking something somewhere across the plateau. The Himalayas stand far off, as the source or barrier of that something.

4. It will radicalise you against flat places

If you’re reading this newsletter, you’re probably quite mountain-forward (c.f. my other essays). If for some reason you’re a flatlander, then a good session on gmaps will beat it out of you.

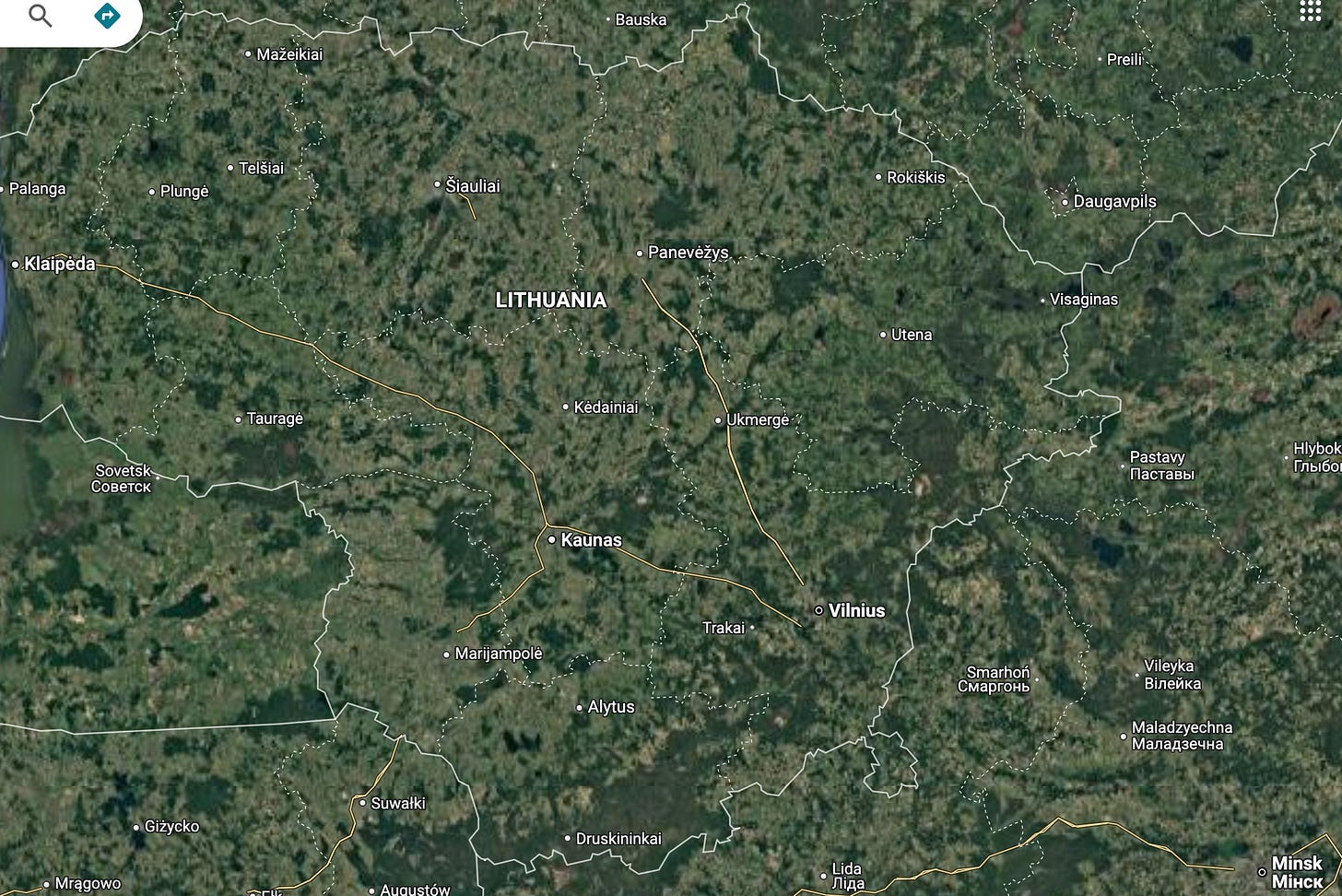

Take Lithuania, for example.

I have never been to Lithuania. I am sure it is very nice. But have a look at that map. Where do you want to check out? If the aliens said they would return you to earth after a session of ship-based torture, but said they could only put you somewhere in Lithuania, would you even be able to pick a spot? It is extremely unzoomable as a country. From orbit there is no feature that grabs the attention. If I’m absent-mindedly scrolling earth, I never end up in Lithuania. It has no magnetism.

However, there is a caveat. The lack can become phenomenal. One of my favourite poems is ‘To a Nightingale’ by R.F. Langley. He starts by observing ‘Nothing along the road.’ Then adds ‘But petals, / maybe’. The more he looks, the more he builds the phenomenon before him, until the birds, insects, flowers all whizz before him. This is sometimes how I feel about looking at Lithuania. To the satellite-minded, there is nothing there. But because the nothingness is so intense, you have to look at it, and then you start to un-nothing it, and it becomes more interesting precisely because it previously tried to escape your attention. Before you know it, you are then zooming in on hamlets at the Lithuanian-Belarusian border. Because there must be something to the nothing.

This expresses something important about the act of zooming. Even though you might think you are choosing a place to zoom because of some feature about the place itself, you are in fact always pushed rather than pulled, encouraged by some desire within you. You look at the villages in Lithuania not because they entice you, but because it fits with whatever mood you have. In this sense, the zoom is not a journey to somewhere new. The zoom always leaves you where you are, in the same room, in the same body.

5. It makes you a border sceptic, but not just in a nice liberal way

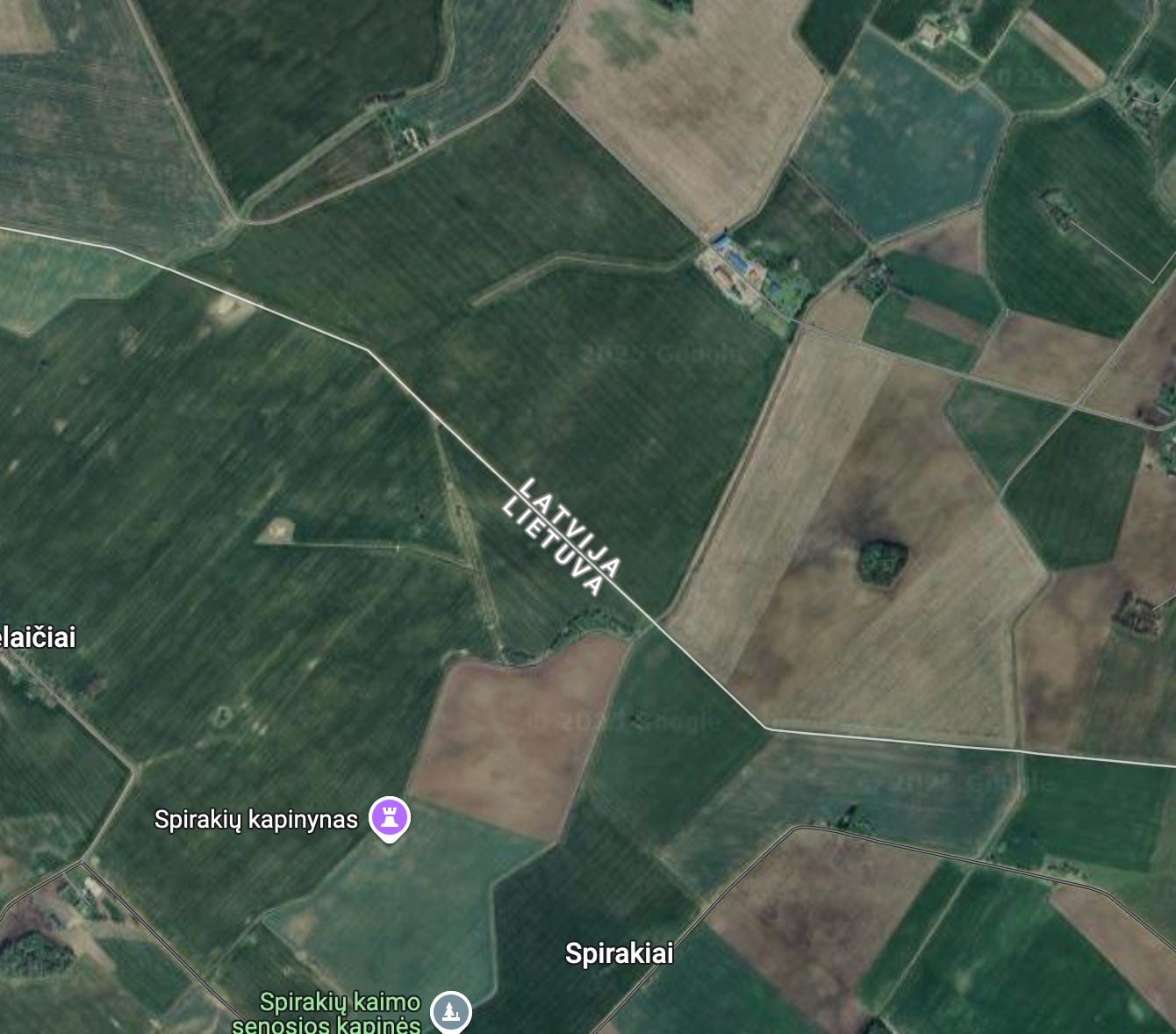

Lithuania was first united into a state in the 13th century. It formed part of a commonwealth with Poland from the 16th to the 18th, and then was under Russian then Soviet occupation until the 20th. Its national identity has been formed through centuries of factionalism and pressures from external empires.

Looking at the borders of Lithuania casually on a Wednesday morning while I sip a tea, I do not intuit any of this history, nuance, struggle and victory. There are no mountains or rivers to separate Latvia from Lithuania. I zoom in. Both sides of the border look exactly the same. The further I zoom, the more I realise that I don’t know. What the fuck is the difference between these two countries anyway?

Looking at places from satellite imagery encourages border scepticism, but not a John Lennon border philosophy. It is not about imagining a world where Latvia and Lithuania share their gorgeous green fields. Instead, I cannot help but question the legitimacy of the history and struggle that went into settling those borders. It’s not that borders seem important enough to hate, pace Lennon. It’s that they barely seem to exist at all.

You can see how imperial administrators, fresh out of Haileybury, armed with a smattering of Persian and a dark pen, felt confident drawing lines all over the Arab world. Gmaps gives you the nation-assigner’s balls to gerrymander a century.

5. Places don’t exist if they don’t have StreetView

It’s not just borders that gmaps conceptually deletes. There are whole countries which can be deleted, but this time its via not showing something rather than showing it. Now and then, I read in the news about some niche-r country, and it can happen that I am surprised to find I had forgotten about its existence despite my gmaps habit. Such countries are always those without StreetView coverage.

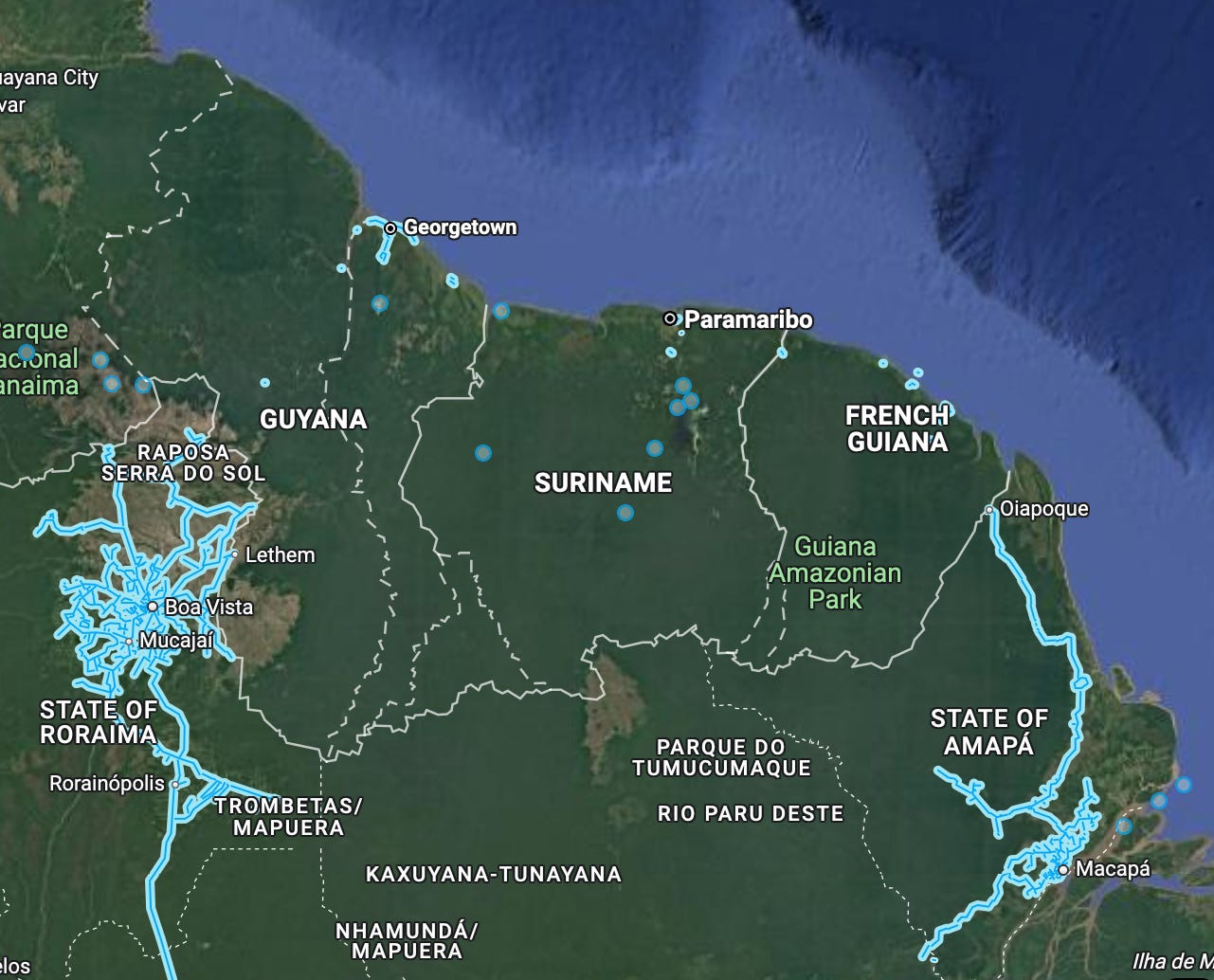

For example, Suriname has no StreetView, and only a smattering of PhotoSpheres. How often do you think about Suriname? What is it like? How many people in the UK remember that the Surinamese speak Dutch? (Yes!) Its neighbours too on the northern coast of South America are also quite uncovered by gmaps. How often do you think about French Guiana?

It must be said however that not all uncovered countries recede from view. The obvious one is China, which it has become illegal not to think about all the time. The other one is DRC, which is ironic and sad given the heart of darkness baggage.

6. You shouldn’t overcorrect for Mercator distortion

We all know that Greenland is not in fact the size of Latin America, and that its map-based sprawl is an artefact of a 16th-century Flemish cartographer’s ingenuity.

However, knowledge of the Mercator projection can lead a well-intentioned gmapper astray. Because, while there is some distortion, you ought not to lose sight of the fact that the idea behind the projection is still kind of true. When you look at a map, and think there’s so much arctic, you’re not wrong! The poles are by far the best part of the earth, and deserve the disproportionate share of map-space they get.

Sure, Greenland is nowhere near bigger than China, but then remember: Greenland is basically just one big glacier. Which means there exists a sheet of empty ice basically as long as China! Which is crazy! Mercator distortion shouldn’t make you think the Arctic is manageable and small, because it is not.

When looking at gmaps, you sometimes think you’re breaking through the false consciousness of Mercator, and seeing things for how they are, but that would be to misunderstand maps, and — as I have said — to misunderstand zooming. Everything has a size, and everything is also sized by you.

Mercator also allows places near the equator to surprise you even more than they otherwise might have done. The huge countries in central Africa which do not have coverage — DRC, Central African Republic, Tanzania — they are impossible fully to scale, impossible to compare to places with more complete data like Europe or the USA. But that doesn’t mean they are an more mysterious. As we have seen, places that we think we know about can be just as weird, because those places have more of your expectations they can violate. The map is just structured surprise, endlessly recurring.

Part II coming soon…

Will! This was such a treat to read because I didn't know other people also do mindless (and then sometimes, very intentional) zooms through Google Maps. I loved your prose when you wrote 'it’s a two-finger drag to zoom, which is a gesture I have always liked because it rhymes with beckoning' - how incredibly beautiful!

To share a personal anecdote, I remember having such a great time Google Maps traversing around Mecca - it's a place I'm almost certainly never going to go but one I'm really curious about, and it was really strange seeing how, well, normal it was as a GMaps location. But then I also adore exploring northern Norway/ Sweden/ Finland and various hinterlands. Something about conceptualising all the lives lived that I'll never get to experience is very romantic and melancholy in the best possible way.

And lastly, love the Baffin Island shout-out! I'm sure we'll go at some point. I've had friends go to Iqaluit, though I think flights are something silly like $3000 (CAD).