The Greatest Coincidence in the History of Ice

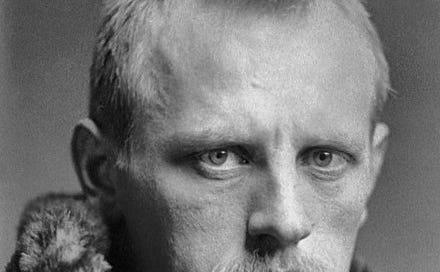

The saving of Fridtjof Nansen and Hjalmar Johansen

I had written a long essay trying to reckon with the physical and spiritual achievement of Fridtjof Nansen, and I became rather excited. I began to tell my friends about it, bubbling over with Arctic fever during an unusually stormy London winter, which made me think about gales cutting across pack ice, violent pressure ridges, the groan of floes as they melt and tumble — but I quickly realised that the essay I had written would not interest them at all. No one — except one Norwegian — had even heard of Nansen, let alone his extraordinary Arctic ordeal of 1893-6.

The story is actually very simple, and probably the most impressive feat of survival ever recorded. It took place at a moment in the long history of Arctic exploration when mouths were unquestionably bigger than stomachs. The polar blunders began in 1845, when John Franklin's exploration of the Northwest passage ended in all 129 crew dying, some eating each other. An attempt at the North Pole in 1871 failed when a storm split the ice, separating nineteen crew members away from their colleagues and consigning them to six months stranded on their floe as it drifted across the Arctic.

In 1881, there was yet another disaster. An American expedition for the pole in 1879 ran into trouble when the ship, Jeanette, was frozen stuck north of the Bering Strait. The pressure of the ice as it moved with the ocean currents splintered and pulverised the ship, forcing the crew to abandon and head for Siberia, where most of them died from starvation and hypothermia. It would have been just another bitter sentence in history, were it not for the fact that some scraps of paper and articles of clothing from Jeanette washed up in Greenland — the opposite side of the Arctic to where the ship had got stuck.

In 1884, Norwegian meteorologist Henrik Mohn speculated in the newspaper Morgenbladet that the debris on Greenlandic beaches might imply the existence of a transpolar current running from east to west. Over his coffee in Christiania — now called Oslo — a young Fridtjof Nansen read Mohn’s article with great interest.1 By day he was a doctoral student in biology, but had only chosen subject because it would afford him opportunities for travel, which was his real goal. To Nansen, all the years of failing to reach the North Pole were both a warning and a challenge. History had left an empty space where he might inscribe his name. He had long incubated ideas for an expedition of his own to the North, and it was in this respect that Mohn’s theory of transpolar drift “struck [him] immediately as the way ahead.”2

It would take a few more years for Nansen to start actively planning for the North Pole. In the meantime he devised and pulled off the first crossing of Greenland in 1888, which won him a tidy batch of medals and prizes from various Norwegian institutions. The reputation thus achieved gave him access to a plethora of potential backers for a subsequent, more audacious expedition, the plans for which he finally revealed in an 1890 address to the Christiania Geographical Society. If Mohn was right about the existence of a transpolar drift, Nansen argued, then a ship could be intentionally frozen into the sea ice, and the crew could sit back while the great forces of the earth carried them to their destination. The crucial point was to build a ship which would not be crushed by the pressure of the floes on all sides like Jeanette had been.

Perhaps this all sounds quite reasonable, and Nansen evidently was a master at presenting his schemes as if they were reasonable, but the scientific character of his plan must not be overstated. The evidence base for the hypothesised transpolar drift comprised only of the pieces of Jeanette found in Greenland, plus an Alaskan Inuit throwing-stick which was also washed up there. It was clear that stuff could float across the Arctic, but no one knew what kind of path it took, and exactly how quickly it travelled. And besides, what about all the bits of Jeanette which didn’t end up in Greenland?

Most people that heard Nansen’s plan thought it was crazy. The only way the expedition could succeed was if this polar drift — which was not guaranteed even to exist — was fast, predictable, consistent, and close to the pole. There was no reason to be confident it was any of those things. Surely someone would only sign up to an expedition so dangerous and profoundly unknown if they felt they impelled by some moral imperative that totally outweighed any rational consideration, some motivation as large as history itself. And Nansen was.

In 1890, Norway was technically independent, and yet it was nonetheless in a personal union with Sweden under the rule of Oscar II, who was not keen to relinquish what control he had over both nations. This arrangement became increasingly under pressure in the late nineteenth century from Norway’s flourishing romantic nationalist movement, a movement that defined itself against Danish and Swedish influence. All the Norwegian artists you have heard of — Ibsen, Grieg, and Munch — came from this period, and their international success was held up as evidence that Norwegian culture and identity was valid.

This sparsely-populated, badly-shaped country, which for centuries had done little but fish and be invaded, needed something to be the best at. Given its latitude, and the Gulf Stream which warms its northern towns and makes them more habitable than Siberia or Canada, it made sense for Arctic exploration to be the arena for national self-expression. “There is global contest for the pole,” declared Nansen to the government in his application for a grant. “May it be the Norwegian flag that first flies over [it]!” This nationalism that was inspiring Nansen — as is often the case with nationalisms — was viewed as the fulfilment of some ancient promise. “Our ancestors, the ancient Vikings, were the first polar explorers’, he explained, going on to suggest that “[t]here is possibly some of the aspiring Viking blood in me.” Describing the men who first explored the Arctic centuries before, Nansen uses the word nordmaend, which is also the demonym for ‘Norwegian’ — the language of nationalism insists upon the identity of the ancient and the modern.

Nordmaend literally means ‘north men’, which points to another crucial component of this nationalism: the sheer fact of northernness was a component of Norwegian identity. Poet Rolf Jacobsen summed it up in a famous line: ‘This country is long. Most of it is north.’ (Det er langt dette landet. Det meste er nord). For a nation which defines itself simply as The North Country, there is something appropriate, harmonious, about being the conqueror and domesticator of the North Pole, i.e. the very definition of northernness.

Nansen was a powerful writer, with a weird knack of using nationalist and romantic cliché without blushing and making his audience cringe, and found it easy to surf the nationalist swell building in Christiania. Soon enough he had a large enough fund to launch his polar expedition. He spent much of the money on what was undoubtedly going to be the most important component: the ship. Other ships that had made attempts at the pole had been crushed by the ice because their hulls had plunged deep into the water, and thus exposed lots of surface area to the ice. Nansen’s idea was to build a vessel with special rounded hull which, under pressure from the ice, would not buckle, but would simply be pushed up and out of the ice pack. He called it Fram — ‘forward’ in Norwegian.

Fram left Christiania in June 1893. There was a crew of twelve men, and they had taken supplies to last them for five years, but really no one knew how long it would take. They sailed up round Norway, and after some months were stuck in ice north of Siberia. The crew busied themselves with stoking, hauling, hunting, cleaning, all the while keeping an eye on how the hull was withstanding the ever-increasing pressure. Winter came upon them, with muscular ice choking their little wooden speck. Miles of monotone flatness gave out in all directions, open air, and little movement. But even as the pressure intensified, the ship stayed intact. Nansen noticed it rising further up, week by week. With each inch the craft raised up, the more confident he became.

Even though their ship was now safe on the ice, they were still at its mercy. “Here I sit among the drifting ice floes in the great silence,” Nansen wrote one day, “and stare up at the eternal courses of the stars, and in the distance see the thread of life becoming entangled in the complex web which stretches from the gentle dawn of life to the everlasting silence of the ice.” Having no influence over immediate progress of the ship, it is no wonder that Nansen’s thoughts turned to eternity.

Initially, progress on the ice floe was promising, but soon Nansen began to doubt the idea that the drift would carry them close to the pole and back over towards Norway. During the winter they realised that, instead of floating north, they were in fact mercilessly zig-zagging, and by January they were further south than when they started. There was nothing they could do but wait. The polar night finally passed. In the spring of 1894 they began to drift north again, but at a rate of barely a mile a day. At that speed they would not get near the pole for years.

Day by day, Nansen’s hopes of an ice-bound journey to ninety degrees north faded, and he began to consider how to salvage something from the trip. In the event that the ship itself couldn’t reach the pole, he suspected that a smaller team might be able to leave and reach it on skis. However, this smaller team would have to make a horrible, terrifying bargain: they would have no choice but to say goodbye to the Fram forever. Since the ship would be drifting around in a pattern which they could not predict, those that left it would have no way of knowing where it had travelled to. If a smaller party were to make a dash for the pole, it would have to continue on and past it, and somehow escape the Arctic on its own.

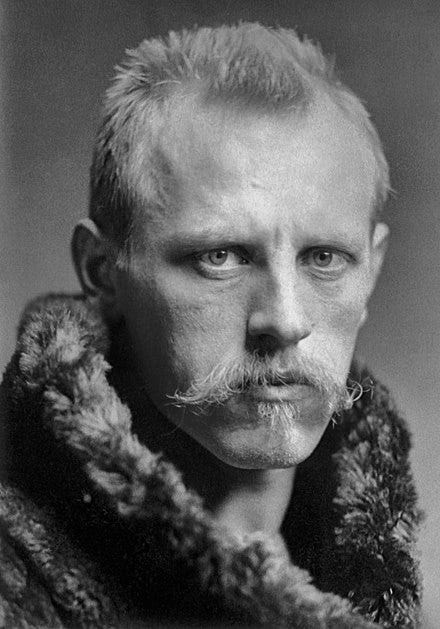

After a second winter in the ice, Nansen decided it was time to strike. He asked Hjalmar Johansen, Fram’s stoker, to join him in a two-man push north. Johansen agreed immediately. They got together twenty-eight dogs, three sleds, and two kayaks. The idea was to reach the pole and then ski on, aiming to reach the northerly archipelago Franz Josef Land from which they could attempt to kayak to Svalbard. Once again, we can imagine Nansen making it sound reasonable and even attractive, deploying his lovely romantic phrases in his explanations to the crew. And yet in his history of the Arctic, Fergus Fleming called this plan ‘one of the most foolhardy in polar exploration’. The pair would have to be alone for six months on the ice, skiing to places no human had ever been. They would then then need to escape over open Arctic waters in untested kayaks, covering distances of hundreds of miles, to reach…where? Siberia? Svalbard? Greenland? All places which were frozen, horrible and lethal. Places which could kill you just as easily as the Arctic ice.

On March 14th 1895, the pair departed. Nansen’s tone in his diaries at this point is ambivalent. Turning round to look at the ship as they departed, he “wished to follow back, and once again be seated in the cosy warm salon”. His indecisiveness meant that, at the last moment, he did not bring their wolfskin outer garments and instead relied on wool, which proved to be a mistake. Their wool layers quickly got soaked and froze into a solid casing of ice which made moving extremely difficult. At night in their sleeping bags the ice in the wool melted, leaving them shivering in a puddle of cold water.

After covering twenty miles a day for the first week or so, Nansen was elated. The ice was firm and smooth, not broken up into huge pressure ridges as it was further south. The dogs pulled the sleds with vigour. It was nearly light all the time as the Arctic summer arrived, and the visibility was clear. Klar som vanlig (clear as usual) is what Nansen wrote in his diary for a few days in a row. “If it all goes like this, it will all go like a dance” (gå som en dans).

On March 28, Johansen took a reading of their latitude. He frowned at the chronometer, and took another. He told Nansen what he found: 85º 35’ N. They were both confused. They ought to have been in latitude 86. Disturbed, they decided to ignore it — instruments were often wrong, and measurements had a way of working themselves out. A week later, they tried again, and they were still only at 85º 59’ N.

Reluctantly, they accepted their situation. Just as the ice pack had been moving unpredictably and taking the Fram south, the same was happening to the men moving on skis. They weren’t fast enough to outpace the current, being pulled south and west at a greater rate than their northward progress. The strange and whimsical drift meant that they would never truly be sure of where they were going and at what speed. To make matter worse, the ice started deteriorating. The summer warmth was melting the top layer, making it slushy and impossible to ski on (a similar problem would beset Shackleton in Antarctica twenty years later). Progress was slowing, and they were being pulled back all the time.

On April 8, Nansen admitted defeat. “We won’t be able to go further north”, he wrote. They cheered themselves with a meal of lapskaus, bread and butter, chocolate, and red whortleberries. They took one final reading of their location: 86º 13’ N, a new record by almost three degrees. Even though their bid for the pole had failed, they had achieved something: the furthest point north by any human.

A few days into the retreat things started going wrong. Both men had forgotten to wind their clocks, so they lost track of the time. Given that their only way of knowing their longitude was to compare the time with the position of the sun, this nearly had disastrous consequences on their route finding to Franz Josef Land. Johansen had to guess how long the clocks had been stopped and rewind them — remarkably, he guessed within a few minutes of the actual time, meaning that their navigation was not ruined. Nansen dropped his compass and spent hours ski’ing back to find it. Their progress got slower as their skis kept sinking into the slush. ‘This is getting worse and worse,” Nansen wrote on a day in June in which they had travelled barely a mile.

Finally in July, the horizon, which had been a straight white line for the 132 days they had spent on the ice, exhibited a tiny bump. “At last we have seen land,” celebrated Nansen in his journal. “And this white line, which has spread over the sea for thousands of years, and which for thousands of years will continue to spread in the same way — now we will leave it.” Johansen, in an act of Babylonian extravagance, changed his underwear for the first time in four months. An inlet of water opened up in the ice through which they could steer their kayaks all the way to the island. They shot all their remaining dogs and climbed aboard. As they paddled, they did not know if they were lost or saved.

On the 26th of August they landed on a windblown cape which bore no resemblance to anything on their maps. Even though they had hopes of progressing further south, Nansen was already contemplating this being more than a temporary camp, evaluating their “prospects if we should be forced to winter here.” They sailed around the island, deciding between heading for islands further south or building winter quarters. Their issue was that, even though were off the ice, their movement was still slow. The winds were just as brutal as before, and the air just as cold. What’s more, they had to spend vast amounts of time hunting and butchering seals, walrus, and bears. This was so that they had food and fuel that could last them no matter what happened — storms, sickness, winter. They were slowed by their caution.

Nansen made the decision at the beginning of September. “The surest thing was to start preparing for winter immediately, while there was still good access to game, and here was indeed also a good winter place.” They had by now assembled a good store of meat and blubber. For shelter they dug a hole three foot deep, and built stone walls around it. With driftwood they assembled a roof which they covered with walrus hides. October came, and the pair settled into a routine of making their last preparations: hunting, skinning, digging, drying. Fittingly, Nansen’s writing here becomes suffused with ominous absurdity: “Johansen shot a bear, which then “bit and tore at its own hind legs until blood ran from them… the hindquarters hung and dragged behind, and it could only drag itself forward on its front legs, and it went around in circles.” The world they faced was terrifying, and it also made no sense.

“The sun sank lower and lower, until on October 15th we saw it for the last time above the ridge to the south; the days grew rapidly darker, and then began our third polar night” — it had been more than three years since they had seen Norway. They shot two more bears and reinforced the roof with the fresh hide and made new sleeping bags from its pelt. The temperature began to plummet. At night it was minus twenty at the warmest.

“There was not much variety in our life. It consisted in cooking and eating breakfast in the morning. Then, perhaps, came another nap, after which we would go out to get a little exercise.” They slept on bearskins. They heated themselves by a little blubber stove. They read Johansen’s navigation tables over and over again: columns of numbers in print as their only remaining artefact of civilisation. Two men in a hole on the beach in the Arctic, warming their hands over burning fat, hundreds of miles from anyone else. If they even knew where they were.

On the 22nd of December, Nansen watched the aurora. “Is it the fire giant Surt himself, who strikes his mighty silver harp, so the strings quiver and glitter in the shine of Muspelheim's flames? Yes, it is a harp playing, silent and eerie in light and colours, wildly storming in the night. But sometimes also gently playing like softly rocking silver waves, carrying dreams to unknown worlds.”

Nansen’s diary becomes empty here. While before, when slogging over the ice, he could fill hundreds of words with descriptions of pressure ridges, barking seals, and moving clouds, each day of that winter was nothing, pure duration. They sat in their shelter for eight months. Eight. “The very emptiness of the journal really gives the best representation of our life during the months we lived there.” Speculation can tell us almost nothing about what this was like.

Spring arrived, but very slowly. They began to move their bodies and leave the shelter. In order to prepare for their onward journey they started to economise on food and fuel. Every bear they saw they hunted and shot. Walruses and seals in the neighbourhood were similarly unlucky. The pair set off on 19th May 1896, island-hopping the archipelago, setting up camps on each as they wound their way south. On one, Nansen forgot to tether the kayaks down and they blew off into the sea. Since the kayaks were their only hope of escape, he had no choice but to strip off, jump in and retrieve them. He lay in his sleeping sack for hours after, frozen, eating guillemot soup.

They continued to paddle between islands with relative ease — until a pack of walrus swam up beneath them and began to hassle their craft. Before the men could shoot them, their tusks had cut deep gashes in the kayaks which began to fill with water. They managed to get to boats shore, but their southward journey was delayed by four days as they repaired the craft. On the morning of the 17th of June, on the fourth day of their emergency stop, Nansen heard something like a dog barking. “A sound suddenly reached my ear so like the barking of a dog that I started. It was only a couple of barks, but it could not be anything else.” Johansen couldn’t hear anything, but Nansen insisted they ski over the headland to investigate. Indeed, it was a dog. More importantly, behind the dog was a man.

This man was Frederic Jackson, a British polar explorer who had been sent to map the Franz Josef archipelago. As he approached Nansen along the icy beach, Jackson thought he might be a stranded walrus fishermen, but as they spoke, he realised that it was, in fact, someone he already knew.

“Aren’t you Nansen?” he asked, astonished. They shook hands.

The two had met in 1891 at the Royal Geographical Society in London where Nansen was explaining his theories of transpolar drift. At that meeting, Jackson had actually asked Nansen if he could come with him on the Fram, but Nansen said no. “The effect of this friendly rebuff,” Jackson wrote, “was to make me determined to run my own show, and forthwith I set to work to organise a Polar expedition of my own.” Jackson’s “expedition of my own” was precisely this one that had taken him to the beach in Franz Josef land, where he now stood in front of Nansen once again. “Nansen had set in train the events now unfolding on the ice,” Huntford points out. In a roundabout way, Nansen was his own rescuer.

This meeting is an astounding coincidence. After having spent years in the most inhospitable and brutal landscape on earth, Nansen was rescued because of a chance encounter with a man who he personally knew. In the literature, this moment is often compared to Stanley meeting Dr Livingstone, but it is surely much more incredible than that. Stanley was looking for Livingstone, and they were in a place were other people lived, whereas Nansen and Johansen were somewhere that only a handful of humans had ever been in all history. Livingstone did not have to live in a hole for eight months during the polar night just to meet his rescuer.

Johansen and Nansen returned to Norway after nearly four years in the Arctic. Meanwhile, the Fram came unstuck from the ice, and Nansen and Johansen joined their crew on the boat in August 1896, sailing south along Norway’s coastline in triumph. They hadn’t made it to the pole, but they had made it further north than anyone before them. And after years of being frozen, no one was dead.

Thank you for reading. Please have a look at my other pieces: here about Guinness drinking in Patagonia, here about the greatest mystery in the Himalayas, and also an interview with a rock climber who doesn’t use his hands.

Much of my history of Nansen outside of the expedition owes to three books: Nansen, Roland Huntford (Abacus, 2001); Ninety Degrees North, Fergus Fleming (Granta, 2002); Limits of the Known, David Roberts (Norton, 2017)