Who was the most indebted person in history?

"What eye has wept for him? What heart has heaved one throb of unmercenary sorrow?"

When George III ascended to the throne in 1760, Britain had just finished her Annus mirabilis in which she achieved a number of crucial victories in the Seven Year’s War.1 Best of all was the Battle of Quiberon Bay, which so devastated the French navy that it scuppered any dreams they might have had of invading Britain. All this success was expensive, however. The national debt ballooned from £77 million in 1758 to more than £98 million in 1761, leaving the new King with the prospect of the country running out of credit. Consequently, his first political priority was to address the national debt, and put Britain in a financial position to back up its military one. They aimed ‘lighten the burden on posterity as soon as they dared’, in the words of one historian.

As all this was going on, in 1762 the King had his first son, George, the Prince of Wales. The King, while uxorious, had a complicated attitude towards his children. The younger George would later complain that he was kept in baby-clothes even when grown up and all his friends were dressed properly. The Prince was regularly dressed in gold drawers and told to stand on ceremony on occasions such as the King’s birthday or the anniversary of his coronation. Any affection the King had ‘was heavy-handed and conditional on good behaviour’, which the prince rarely displayed. The King deplored his son’s execrable German, especially frustrating given that technically they were still Electors of Hanover.

In his late teens the Prince was looking for a release, and it came in the form of Whig MP Charles James Fox. One of the reasons why 18th century Britain is a particularly appealing object of study is the number of scoundrels who made it to positions of influence, and Fox is exemplary in this respect. Fat, short, hairy, he introduced the susceptible Prince to Whig high society, i.e. gambling, drinking, sexual extremity, and a style of politics we might now call ‘trolling’. One friend said of him that his chief characteristic was the ‘determination never to put himself under the disagreeable restraint of one minute’, while another admitted that ‘he had no heart’. Fox and the Prince got on so nicely that they managed to share a number of mistresses.

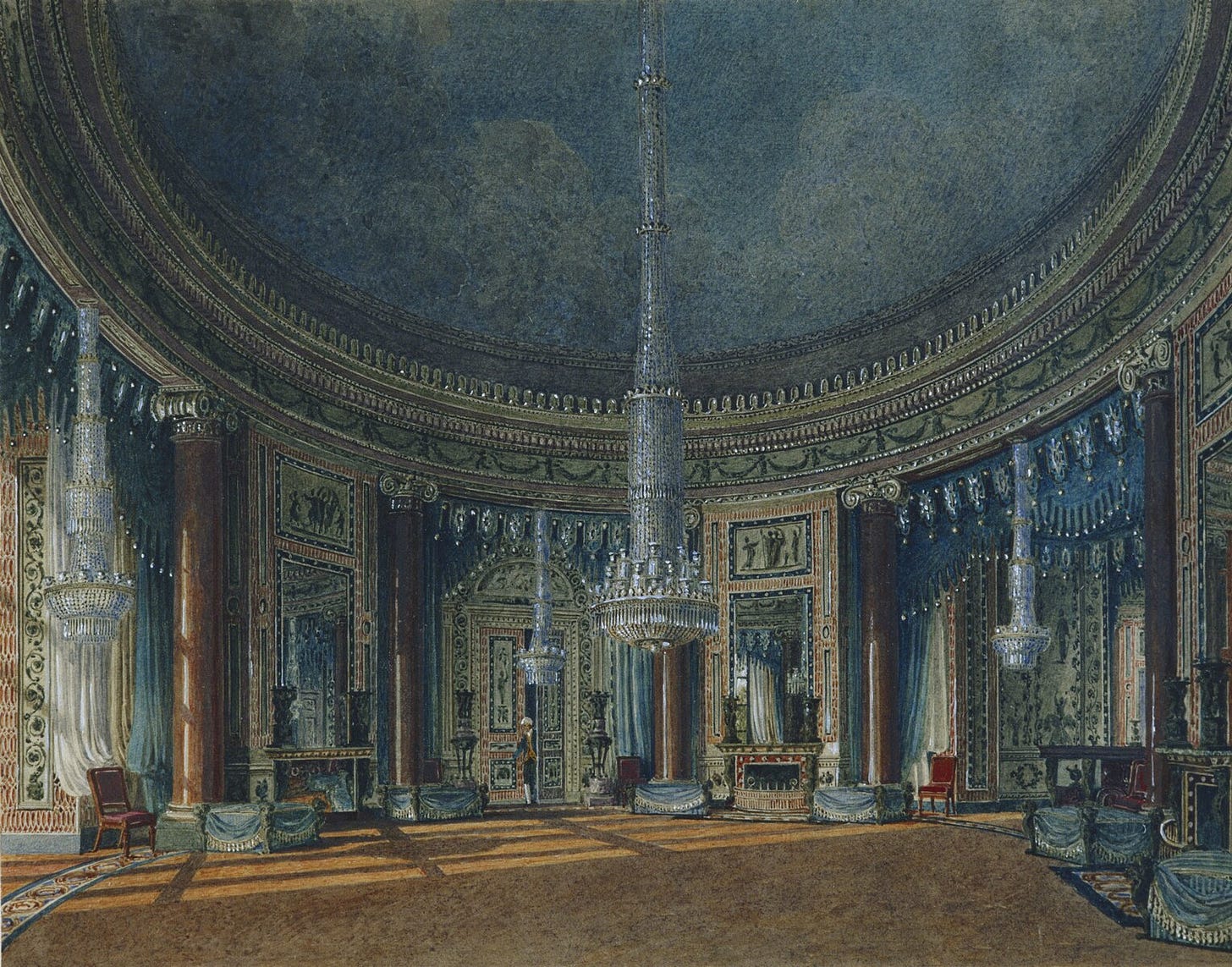

In 1783, at the age of 21, the Prince was granted Carlton House as his official residence overlooking St James’ Park. The King insisted that his son limit himself to ‘painting it and putting in handsome furniture only where necessary’, but he can’t seriously have expected him to listen. From Fox and his circle the Prince of Wales had learnt the arts of profligacy and unreasonableness, and of course such an attitude would extend to his manner of residence. He made the big early call of commissioning architect Henry Holland to lead the renovations. Holland was mainly famous for his fashionable uninterest in budgetary restraint, which was the sort of thing which made you very successful with dissolute aristocrats in the mid 18th century. Within weeks he had drawn up plans to make Carlton into the most impressive and expensive house of the era.

The facade was made into a Corinthian portico, and inside was an impressive entrance hall, ‘an octagon with a sweeping double staircase….fringed with Ionic columns of Siena marble‘. It drew comparisons to Versailles, both in praise and insult.

As Holland’s plans were being realised, it became clear that the £50,000 per annum the Prince had been granted was insufficient to fund the building. And so he chose the most sensible path for a man of his station: keep spending as if he had the money, ‘on the principle that if his father did not allow him enough then his father would have to pay the debts which he was driven to incur’, as E. A. Smith explains. The irony, that while the Crown was striving to reduce the national debt the Prince of Wales was striving to increase his personal debt, was not lost on George III, and neither was its bitterness.

On this single occasion in his life, the Prince of Wales found a principle to which he could adhere. He continued to spend for the next five years as if there were no consequences associated with it, able to keep borrowing because his creditors rightly assumed that he would not be left to go bankrupt by the Crown. By the summer of 1786, his debts amounted to £269,878, which Andrew Roberts reckons as ‘equivalent to more than one quarter of the UK’s annual non-military expenditure.’ In 1787 Fox, looking out for his old friend, managed to get a bill through Parliament to settle these debts via a one-off grant. Yet by 1792, the Prince was back in the same position, far deep in the red. This time he was £400,000 down, which would be around £60 million today: a good Premier League footballer, or a few houses in Mayfair.

The Prince of Wales became George IV in 1820 on the death of his father, but his largesse did not abate upon accession to greater responsibility. He declared that Carlton House, despite all the expense and effort, was after all not adequate to his needs, and had it demolished in 1826. He took to wearing a corset of whalebone in order to slim him down for public appearances. Sir David Wilkie, the Scottish artist who painted George in 1822, likened him to a ‘great sausage stuffed into its covering’. When he died in 1830 he left £1 million of personal debt, hitting £200 million mark today.

All this leaves George IV in the position of potentially being the most indebted individual in British history. There are other candidates, of course. For example, the splendid 2nd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos was declared bankrupt in 1847 with debts of over £1 million. He had to sell all his properties, including Stowe House in Buckinghamshire which then became Stowe School (giving us alumni such as Branson, Monbiot, Niven, Worsthorne and Superman). The Duke’s financial ruin made excellent newspaper scandal. As one paper put it, he ‘lost everything except his name’. His name was Richard Plantagenet Campbell Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville.

Yet the difference between the Duke with the never-ending name and George IV is that one was forced to declare bankruptcy and the other was not. There is something peculiarly British about accruing this much personal debt and getting away with it. Being a constitutional monarch in the 18th century, George IV could not assimilate his personal debts into the sovereign debt; his personal spending was not national spending. Other monarchs — such as Louis XIV or Frederick the Great — were able to do more of this, with the obvious exception of Louis XVI who lost his head for his efforts. And yet, given that he was heir apparent and then monarch, creditors were banking on the public/private separation of George’s finances being merely an administrative question, and that the private debts would, when push came to shove, be assimilated into the public de facto. In essence, George IV’s creditors were betting that the adjective in constitutional monarchy was less important than the noun.

Thank you for reading. Please subscribe or like the post, it helps a lot. I have other posts here about the greatest mystery in the Himalayas, an interview with a rock climber who doesn’t use his hands, or AI and novel writing.

This article borrows heavily from E.A Smith, George IV (Yale, 2000) and Andrew Roberts, George III (Bloomsbury, 2023).

"Betting that the adjective in constitutional monarchy was less important than the noun." is such a pity, well-put ending 🤌🤌🤌